This article is the first in a Huffington Post series examining the state of Black America.

WASHINGTON -- Elijah Cummings, 62 years old, has lived and seen the

best -- and the worst -- of what this country means, offers and does to a

black man. He knows the promise and pain of Black America.

His parents were Southern sharecroppers who moved to Baltimore for a

better life. The budding civil rights movement was active in the city,

and schools and public facilities became integrated when he was a boy.

They were excellent, and he went on to become student body president at

Howard University, earned a law degree and now serves as a Democrat in

the House, representing the city in which he grew up.

He recently took his 86-year-old mother, Ruth Cummings, to meet his

close friend, Barack Obama. A Pentecostal preacher, she told the

president, "I want you to know, son, I pray for you every day."

"She called him 'son'!" Cummings recalled with a laugh. "I said,

'Mom, he's the president.' She told me it was the best day of her life.

It blew her mind to meet a black president."

But as Cummings rose -- indeed, as Barack Obama rose in Chicago -- Baltimore fell.

Cummings' district, which is 60 percent African-American, encompasses

block upon block with abandoned, boarded-up housing.

The congressman lives on one such block. Schools and other public

institutions are under crushing financial pressure. Poverty, joblessness

and incarceration: all rampant, and in many cases worsened in recent

years of recession.

"The unemployment rate in my district among African-American men is

40 percent," he told me. "Forty percent!" And that doesn't count the

many men serving hard time in prison, often for victimless drug crimes

that carry stiff mandatory sentences. "The criminal record makes it

hard, if not impossible, for them to get jobs after they get out," he

said.

Gun violence struck Cummings' own family in 2011. Intruders shot and

killed his 20-year-old nephew,

Christopher Cummings, in an off-campus apartment at Old Dominion

University in Norfolk, Va. Two years later, no one has been arrested.

Christopher was a top student, studying criminal justice.

At a memorial service in Baltimore, Cummings pleaded for an end to

violence in the black community. "I consider my nephew's murder a hate

crime," he told me, his voice laced with bitterness. "They hated his

success."

The story of Elijah Cummings is a story of Black America in the

summer of 2013: rising visibility and achievement, power in high places,

but also renewed focus on the persistence, or decay, of conditions on

the streets and in the homes of African Americans. We aren't living in

the colorblind, post-racial society we hoped a black president might

usher in, not when success is so split along color lines.

"We have famous names of outstanding achievement," the Rev. Jesse

Jackson told me. "We have LeBron. We have Jay Z. We have Barack Obama.

But that is not a random sample. What matters is the undercurrent, and

it's pulling our people down."

This is a teaching moment in American life, a teaching summer.

The country, including the president himself, is talking about race

again. It's our oldest and deepest argument, a conversation in black and

white and blood about our original constitutional and social sin.

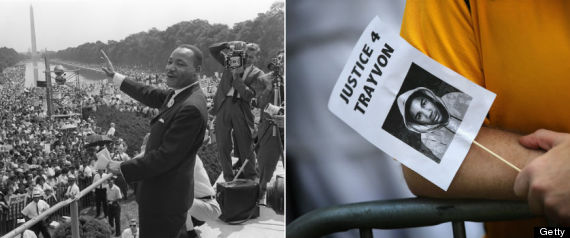

The reasons for its revival now: the Supreme Court, Trayvon, Detroit and Martin Luther King Jr.

In June, the court issued opinions restricting the reach of

affirmative action and the

Voting Rights Act, twin engines of African-American upward mobility.

Earlier this month, a jury in Sanford, Fla.,

acquitted George Zimmerman

of all charges, accepting his claim that he had shot and killed a

17-year-old unarmed black youth named Trayvon Martin in self-defense.

The 2012 shooting and the 2013 verdict divided the country, but united

Black America around the reasonable fear that no black child --

especially no black male -- is safe from the assumption that he is

somehow a threat to the civil order on any street he walks.

President Obama was moved this past week to

offer his own personal testimony

about the casual slights he had suffered and the fears he thought he

had engendered in whites in passing encounters earlier in his life.

"Trayvon Martin could have been me 35 years ago," he said. It was a

stunning statement, and a rare attempt by Obama to explain the world

from his black perspective.

Led by the Rev. Al Sharpton, "Justice for Trayvon" protests were planned for this weekend in 130 cities nationwide.

The day before Obama spoke, Detroit

filed for bankruptcy,

owing an estimated $20 billion to creditors. The city of 700,000 --

once it was 2 million -- is over 80 percent African-American and a mecca

of black culture. But the cheerful pop sound of Motown now seems like a

cruelly ironic soundtrack to decline.

Then there is the equally loud echo of political history.

Later this summer, the nation will observe the 50th anniversary of

the March on Washington for "Jobs and Freedom," and in advance of that

milestone, new questions are being asked about whether African Americans

have much more of either than they did on Aug. 28, 1963.

If Dr. King were alive today, what would he say on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial as he surveyed the scene?

"He would say that we are freer but less equal," said Jackson. "He

would remind us of what he said back then, which is that the allies who

joined us to oppose barbarity will not necessarily be our allies for

equality."

In a series that begins Sunday, The Huffington Post examines the pain

and the promise of Black America and looks at how far we have come, and

still have left to go, to reach

Dr. King's longed-for mountaintop.

The stories focus on poverty and joblessness, health care, crime and

incarceration, barriers to civic participation, the administration's

record, education, and black progress against long odds. HuffPost also

seeks to highlight potential solutions to these endemic issues.

Measured against the arc of American history, which includes more

than two centuries of slavery and a third of official segregation, the

legal, political and social advancements since 1963 are impressive, even

astonishing. We are not a perfect Union, but we are less imperfect in

fundamental and decent ways.

"Jim Crow is gone, housing and school segregation are gone, voting

rights are in, millions were registered, blacks voted in a higher

percentage than whites in 2012," Jackson noted. "We have won a lot of

victories."

Racial diversity is accepted as a social norm, good not only for the

soul and society but for the economy and even, if not especially, for

corporate management.

The president, who measures the culture in part by watching his

daughters, took note of the changed tone. "It doesn't mean that racism

is eliminated," he said this past Friday. "But when I talk to Malia and

Sasha, and I listen to their friends and I see them interact: They're

better than we are -- they are better than we were -- on these issues.

And that is true in every community that I have visited all across the

country."

But cold federal statistics add up to a different narrative. It is a

depressing litany, but one that bears repeating. The numbers tell a old

story: It is shocking how little things have changed since Dr. King

started measuring out loud in the 1950s.

Black poverty rates were cut in half from the start of the 1960s

(when they were over 50 percent) to the year 2000, but have mostly been

inching upwards since. In absolute terms, more blacks are in poverty

than ever -- more than one in four of the nation's 44 million

African-American citizens. More than one in three black children live in

poverty, a percentage that rises to well over 50 percent in cities

such as Detroit.

Diversity is a social good but not automatically an economic one if

there is no broad access to capital. "Diversity can be a diversion,"

said Jackson. "I can sit down and eat anywhere in my hometown, but not a

single building is owned by an African American." And there are only a

small handful of blacks who are CEOs of Fortune 500 companies.

Health care numbers are equally bleak.

Infant mortality,

a basic measure of community health, is 1.14 percent among black

Americans, more than double the 0.51 percent among whites. The relative

rates of health insurance and pension coverage for blacks haven't budged

since 1979, according to

Census figures

and the most recent "State of Working America" study. For example, 48.2

percent of whites had health care coverage in 2010, compared with 37.7

percent of blacks.

Changes in the criminal justice and penal systems -- especially the

rise of mandatory sentencing and the privatization of prisons -- have

created an archipelago of incarceration that has trapped a vastly

disproportionate number of black men behind bars. African Americans are

14 percent of the U.S. population, but constitute nearly 1 million of

the 2.3 million prison inmates today, according to a

recent NAACP study.

"If current trends continue," the study says, "one in three black males

born today can expect to spend time in prison during his lifetime."

Education is a more hopeful tale, at least at first glance. In 1975,

40 percent of African-American high school graduates enrolled in

college; by 2008, that percentage had risen to 56 percent,

according to the College Board.

But overall, only 16 percent of blacks have at least a bachelor's

degree, a rate half that of whites. After decades of diligent effort and

the advent of need-blind admission, the Ivy League is 7 percent black,

still only half the percentage of the overall population.

Violence remains rampant. Blacks were victims in nearly half of all

homicides, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Serious

violent crime against black youths was more than twice that against

white youths. That much of this violence is black-on-black is no solace.

So how far have we really come?

In 1963, Dr. King declared on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial that African Americans were "still not free."

Five years later, in his posthumously published book,

Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?, he depicted the life of African Americans, especially men, in a way that seems alarmingly current:

"Of the good things in life he has approximately one half those of

whites," King wrote, "of the bad he has twice those of whites. ... When

we turn to the negative experiences of life, the Negro has a double

share. There are twice as many unemployed. The rate of infant mortality

(widely accepted as an accurate index of general health) among Negroes

is double that of whites." And so on.

Such statistics remain all too real to men such as Elijah Cummings, who sees them vividly in his Baltimore district.

He told me that he has pressed the president, whose campaign he

oversaw in Maryland in 2008 and 2012, to speak out and do more on what

Jackson called "the undercurrent." Cummings said, "He thinks he has

accomplished a lot, and there is only so hard I can press him."

But Obama now seems to be awakening to the need to speak openly from

the African-American perspective, and Cummings insists on seeing the

promise beyond the pain, based in part on his own youth.

For Cummings, the first steps on the still arduous march to true racial equality began in a wading pool in the late 1950s.

Back then, he was just a young boy whose parents -- strict

Pentecostal preachers both -- had come north from South Carolina in the

1940s to ensure that their children would receive a decent education.

Each summer, in the soupy Chesapeake heat, Elijah and the other black

children would crowd into a tiny wading pool in their poor South

Baltimore neighborhood. "It was so crowded that we had to take turns

stepping into it," Cummings recalled.

Until one day Juanita Jackson Mitchell arrived. Her husband was

Clarence Mitchell, a close associate of Dr. King, a lobbyist for the

NAACP in Washington, and a man who ultimately deserves major credit for

passage of most significant civil rights legislation of the 1950s and

1960s. She was a lawyer -- the first African-American woman admitted to

the bar in Maryland -- and a fiercely effective civil rights activist in

her own right.

"She came by one day and held a meeting of us kids and our parents,"

Cummings recalled. "She said that only a few blocks from us was a much

larger pool, with deeper and cooler water, and didn't we want to swim in

it?" he remembered.

"She said, 'Now the only problem is there are going to be some people

in that pool who don't want you to be in it with them.' We kids didn't

know what she was talking about.

"It took us seven days of trying, but we finally integrated that

pool. And that was my introduction on civil rights. Change does happen."

Ashley Balcerzak contributed reporting.

Posted: 07/21/2013 12:11 am EDT | Updated: 07/21/2013 1:09 am EDT